little did we know (2013)

a book project in development

little did we know (2013)

a book project in development

Leila Conners, director of The 11th Hour, started out in international politics interviewing heads of states, Nobel laureates and other members from what we call the 'global elite'.

From very early on and for most of her twenties she was exposed to their thinking and noticed that the deeper thoughts from a lot of these people were much more profound and forward thinking than the press would report on. She concluded that a unifying element to international dialogue was the environment, because it is the one thing we all share, we all rely on and that we can't avoid as a global humanity.

She saw how this growing, worldwide consciousness about the environment was a unique experience for international politics and realized that this topic was really going to be the conversation that would bring the world together.“

James Jandak Woods, director of Crude Impact, went to Ecuador to meet indigenous people who were trying to protect their pristine rainforest from logging and oil exploration.

It was really inspiring and incredibly beautiful. The people were so integrated with nature because they look to nature for their food, their medicine,... none of their stuff is manufactured. It's taken out of nature and naturally goes back in and when he listened to how they felt about their land he thought; 'Man I wanna do something about this. I want to make the world aware, the way I was made aware about the terrible implications of oil exploration in these countries because we've absolutely devastated the place.'

He felt he was responsible and guilty for unconsciously using energy and he wanted to prevent people from having that same confrontation later in life. He wanted people to be able to say; 'I knew about this, and I did something about it.'

Director Leila Conners arrives for the gala screening of ‘The 11th Hour’ at the 60th Cannes Film Festival with Leonardo DiCaprio, writer and producer of the film. © Reuters

Thanks to the environmental movement in the early seventies, a lot of kids received recycling and eco-programs at school and Chris Paine, maker of Who Killed The Electric Car grew up that way, with parents who cared a lot about the environment.

He decided never to own a new car unless it was electric and when General Motors announced they were going to put out an EV (Electric Vehicle) he arranged everything to buy one.

When it finally came out in 1996 he drove one around the block and just couldn't believe how much better it was than he had even expected, especially cause it was so fast. He knew the car would be great because it didn't pollute but he didn't think it could be so much fun too.

He leased the car cause GM wouldn't sell it and after driving it for 5 years GM killed it. Ironically there was a smog alert that day... Don't let your kids play outside,

gasoline cars are making your life miserable

They were destroying the electric car on the same day that urban areas were suffering excessive pollution from car exhaust.

Dan Neil, Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk, director Chris Paine, CEO of Yokohama Carlos Ghosen and actor David Duchovny speak about the film ‘Revenge of the Electric Car’ during the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City. © Dario Cantatore/Getty Images

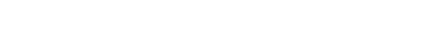

Patrick Rouxel receiving the Grand Taton Award for his film ‘Green’.

Patrick Rouxel, maker of Green, had been working in the film industry doing special effects when he felt the need to do something meaningful, something he truly loved. At 35, the first thing that came to mind was making documentaries on wildlife because he had always loved animals and he felt at home in the wilderness. So he bought a little camera and set off to a national park in Sumatra for a few weeks.

While he was filming the animals he heard chainsaws within the park and he started following the loggers to the sawmill and to the ports. He saw all the wood that was being chopped illegally from Indonesia's national parks being exported to places like Rotterdam and other western cities.

He found out that 75% of all logging in Indonesia is done illegally and that if you buy anything from Indonesia made of wood whether a beautiful teak table or a flooring for your house, most chances are that people and animals have lost their habitat for it.

Before Sam Bozzo started filming his documentary World Water Wars aka Blue Gold, he had only made narrative films. He had no environmental background, knew nothing about non fiction films and nothing about a water crisis. As a matter of fact, he had just started writing a sequel to the science fiction movie 'The Man Who Fell To Earth' in which David Bowie plays an alien coming to Earth for our water, since his planet ran out. The script of the follow up was based upon the idea that Earth in its turn would run out of water and how would the aliens deal with that now that they had taken over? For research, the producer stumbled upon the book Blue Gold and when Sam read it, he was shocked. He had no idea that anything like this was going on in the real world. The information and the stories in this book were more horrifying than what he and his team were coming up with for their science fiction's worst case scenarios.

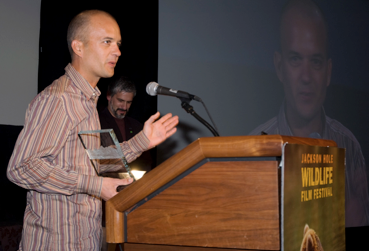

The work Yann Arthus Bertrand, director of Home, did with the photo project Earth From Above transformed him completely. The first thing he understood was that the world was much more beautiful than he could have ever imagined. Flying over endless amounts of vast landscape and untouched natural beauty -in a relatively short time- he was overwhelmed.

He was transformed again when he saw the impact mankind had on the planet. In his generation, he's now 65 years old, he's seen the world population triple. When he was born, we were two billion people, now we're nearly seven. This happened over 60 years after being less than 2 billion for hundreds and hundreds of centuries. There is no other generation who has ever seen or who will ever see this happen, other than his.

He realized that if today, you're not concerned about the future, it's because you don't understand the numbers, or you don't want to see them.

At TED, aerial photographer Yann-Arthus Betrand displays his three most recent projects on humanity and our habitat, one of which is his film ‘HOME’.

Director Stuart Sender and his wife, producer Julie Bergman-Sender promote the first annual Sundance London film and music festival with their film ‘Harmony’, joined by Robert Redford and Charles, Prince of Wales, protagonist of the film. © Bauer Griffin

Bringing messages that aren't necessarily mainstream, into a mainstream context is something Stuart Sender and his wife Julie Bergman, director and producer of Harmony, know how to do well.

When they met Prince Charles of Wales they came to understand his holistic worldview; the kind that connects all people from all around the world, the kind that makes it clear that no one is exempt from what is happening to our planet in terms of climate change, the loss of species and the challenges we face relating to food and resources, the kind that speaks of social responsibility and new ways of doing business and how all these things are interconnected.

Julie and Stuart saw they had a real opportunity to bring this new way of thinking to the masses. To show that what we often think of as being solely environmental problems are in fact part of a much bigger picture. That it is about human experience, about making the most of our potential and about how we treat each other and the world we live in.

Nicolas Vanier, maker of four films on the Arctic territories, always believed that the best way to protect something is to love it with a passion. That's how, he says, we protect our children so well. His first goal when making a film about the Great North is to share his love for those cold territories and for nature in general.

A lot of his films are simply hymns to nature, that show man living in equilibrium with his environment. For one of them, he crossed Siberia by sledge and dogs and chose to hide the sadness, the pollution and all that was destroyed and to focus instead on what beauty still remained.

He made that choice for two reasons: he knows that unfortunately in 15 or 30 years from now it will be a lot harder to show that which has been preserved and two, that showing something so magnificent has much more impact. Those who witness such wonder will spontaneously want to protect it.

Film maker Nicolas Vanier in his film ‘Siberian Odyssey’. © Nicolas Vanier

Barbara Ettinger and Sven Huseby, director and producer of A Sea Change were taken by surprise completely when they first discovered the issue of ocean acidification. They had in fact just finished an environmental film that had completely exhausted them and their plans were to take three months off to really recover physically and emotionally from the four year commitment that lay behind them. But while laying in bed at home reading magazines they stumbled upon New Yorker magazine article titled The Darkening Sea by Elisabeth Couldry. She explained, very detailed what ocean acidification was and what she said was so dark, so alarming and almost too painful to read, that Barbara and Sven couldn’t just let it go. That same night, after a bit of research they called one of the scientists that was referenced in another article on the same subject and they immediately left for a scientific conference on ocean acidification. This was just the beginning of a frightening journey that led to the film A Sea Change.

Director Barbara Ettinger and her husband, producer Sven Huseby in a Q&A after the screening of their documentary ‘A Sea Change’ at the New York Botanical Garden.